How Dogs Learn

Jan 13, 2020

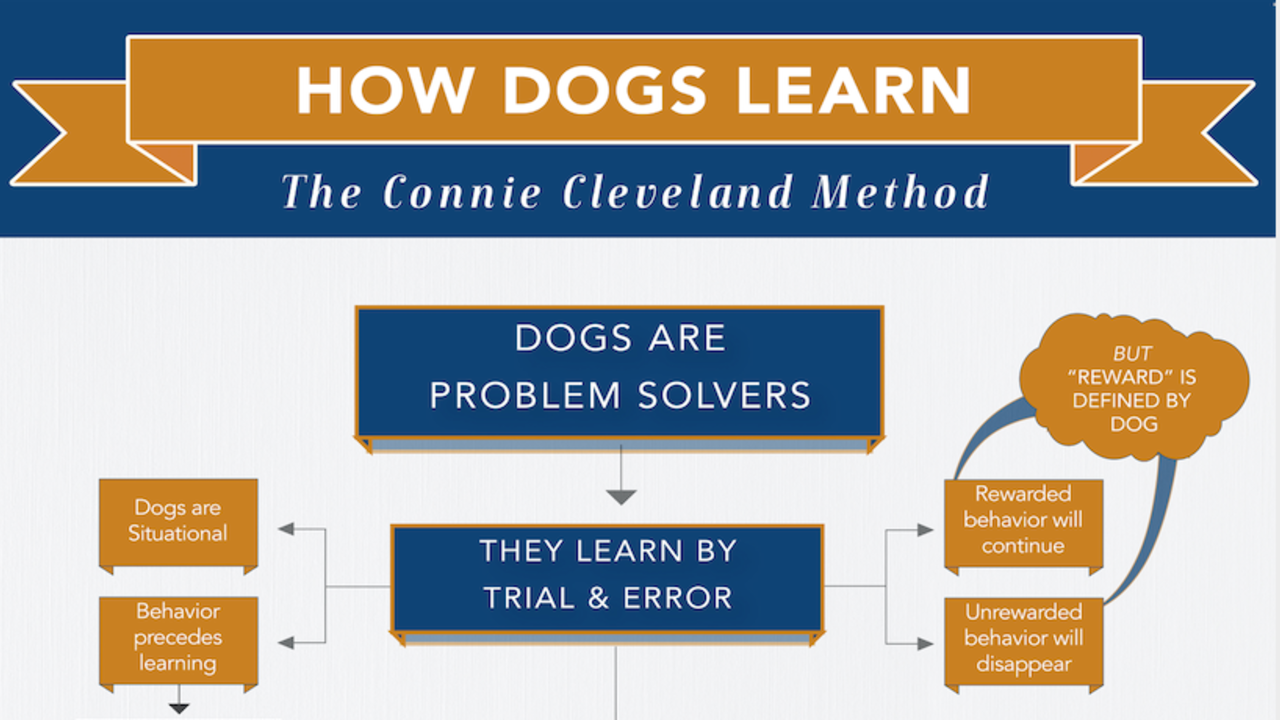

Many years ago, in an attempt to better communicate with my students; I developed a flow chart of training principles that guide me. These principles apply to all venues of dog training. The complete flowchart is at the conclusion of this article.

Dogs Have the Ability to Solve Problems

Have you ever had or seen a dog who could open the latch on his kennel run? How did he learn to do it? First, he believed he had a problem: he was locked in and could not get out. Second, he was determined to solve his problem.

Pretend that you have just rescued a 60-pound mix-breed. You brought him home and put him in a pen in your yard while you made the necessary adjustments to bring him into your home. Unhappy with his confinement, he begins to bark. There is no one around that his barking can bother, so you decide to ignore him. Sure enough, the barking stops, and on a trip by the window, you notice he is digging around the doghouse, and near the gate. “You are wasting your time,” you think, because you have placed wire under the gravel so digging will not be effective.

A short while later you notice he is on top of the doghouse, again finding no escape route. However, the next time you look outside he is gleefully running around the yard. “He has broken out!” is your first response. You examine the run, but there is no evidence of a breakout, the gate stands open. The dog is a problem solver, and he solved the problem of being confined when he did not want to be. You return him to the pen.

If you have ever experienced a dog that solved a problem by opening the latch on his kennel run, you know his second successful attempt at escape is quicker. He may briefly bark, dig, and climb, but soon he is back to jumping and pawing at the gate until he is out again.

Dogs Solve Problems by Trial and Error

This scenario demonstrates that a dog, who believes he has a problem, solves his problem by trial and error. The dog tried to solve his problem by barking, digging, and climbing before he arrived at a successful solution to his problem.

Rewarded Behavior Continues, Unrewarded Behavior Stops

This scenario also demonstrates that rewarded behavior will continue and unrewarded behavior will disappear. The dog did not continue to bark, dig, and climb. He gave up on the “solutions” that did not solve his problem. Instead, he stuck to the solutions that accomplished his goal.

Remember, the reward is defined by the dog. In the sport of obedience, you may find that an unwanted behavior is self-rewarding. For example, you may be tempted to ignore a dog that is mouthing his dumbbell, and reward him only when his mouth is still. However, if he enjoys chewing the dumbbell, this technique will not work because his own enjoyment will outweigh the absence of your reward.

Dogs are Situational

Now consider that you have two pens in the backyard, and the pen that you previously used had a gate that swings from right to left. If you place the same dog, accomplished at opening that gate, in the opposite pen with a gate that swings from left to right, you will severely slow down his attempt to escape, and may even stop it completely.

Why? Because dogs are situational, they can learn to do something under one set of circumstances but not necessarily know how to do it in a slightly different set of circumstances. In this example, the dog has learned to lift the latch with his nose in one location on the gate. When placed in a pen with a gate swinging the opposite direction, he may repeatedly try to hit the hinge with his nose, bewildered as to why his behavior is not achieving the desired outcome.

For this same reason, obedience dogs fail in new locations. Just because he knows, for example, where go-out is in one ring does not mean he will know where it is in a new location or different ring.

Behavior Precedes Learning

Finally, this scenario points out that behavior precedes learning. The first time the dog opens the gate, he does it by accident. He does not understand exactly how he was successful. However, on each successive attempt, he becomes more aware of the exact behavior required. Soon you cannot turn your back before he systematically jumps up and lifts the latch with his nose.

Dogs in their own environment learn what does not work before they learn what does work. The dog in the pen “solved his problem” by trial and error. He tried digging, barking, and climbing on his doghouse. None of the behaviors solved his problem. In fact, he learned what behaviors did not work before he discovered the behavior that solved his problem.

In a training environment, we show dogs what works without giving them an opportunity to discover what does not work. You can call a dog over the broad jump hundreds of times, but if he has never tried running to you or walking through it, he truly does not understand that either of those options are not acceptable ways to solve the broad jump problem.

Dogs Must Learn What Not to Do

In order for a dog to be fully trained, he must understand how to solve his problem, and must understand what behaviors will not solve his problem. This is the definition of proofing: Shaping and luring shows dogs how to perform; proofing teaches dogs how NOT to perform.

For example, you can practice the retrieve over the high jump dozens of times and believe that you have shown your dog how to solve the problem of retrieving across a jump. However, the first time your dumbbell bounces off center, and your dog goes around the jump, he has no idea that he has not solved the problem. Going directly to the dumbbell seems logical to him, and after all, he still retrieved the dumbbell. Just like the dog in the pen, your dog must learn how to solve the off center dumbbell problem when performing a Retrieve over the High Jump, and must also know what does not solve the problem. This is just one simple example of proofing. The same principles apply to every exercise from Novice through Utility.

If you understand that:

- Dogs are Problem Solvers;

- Dogs Learn by Trial and Error;

- Rewarded Behavior Continues, and Unrewarded Behavior Stops;

- Dogs are Situational;

- Behavior Precedes Learning, and

- Dogs Must Learn What Not to Do.

You can use these principles to successfully train your own dog. With this information, you can present each task, or obedience exercise as a problem for the dog to solve, and then help the dog discover the appropriate solution.

Responding to Your Dog’s Behavior

As you teach your dog the steps necessary to learn the obedience exercises, he will respond correctly or incorrectly, and you must learn how to respond appropriately. By definition, reinforcement increases the likelihood that a behavior will increase in frequency and intensity. That’s the goal, correct behaviors more often with more enthusiasm.

Dog Makes the Correct Choice- Handler Uses Positive Reinforcement

When your dog performs correctly, you should respond with positive reinforcement. There is more than one way for you to provide your dog with positive reinforcement: (1) praise that can be followed by a toy or treat; and (2) a conditioned reinforcer (reward marker) that must be followed by a toy or treat.

Praise that Can Be Followed by a Toy or Treat

Praise “can be” followed by a toy or treat but this does not mean that praise alone cannot be positive reinforcement in the absence of a treat or toy. To be a successful performer, your dog must learn to respond to your praise in the absence of a treat or toy.

Praise must be sincere. When you look at the dog heeling next to you, making eye contact, or the dog that is sitting where you left him after you have dropped his leash and circled the ring, you need to show him how much you appreciate the effort he’s making. Your praise must be genuine and expressed with sincere enthusiasm. Your dog knows when you are 100% thrilled, out of your mind excited about something he’s done for you.

What makes a dog “enjoy” being praised? Any behaviorist will tell you that it’s all about pairing the praise with something the dog enjoys. That’s true, but there is more to it than that. Dogs (unlike a lizard or a snake) have a limbic part of their brain that interprets emotion. For example, when someone gives you a compliment, dopamine is released in your body. The dopamine produces excitement and makes you feel good. Dogs experience the same reaction. When you “compliment” your dog by providing positive reinforcement, dopamine is released and he becomes excited. Over time, he will learn to love activities that generate your praise.

I can’t leave the subject of praise without pointing at what praise is not.

- Praise is not obligatory. Do not say “Good Dog!” unless you mean it, if you don’t feel it, don’t waste your breath. Your dog will know that you are not sincere.

- Praise should not start wanted behaviors. Praise rewards existing behaviors. A cheerful “hurry, hurry, hurry!” does not cause a lagging dog to speed up, it tells him it is okay for him to lag.

Promise me that you will only praise with sincerity. Save your praise for the times when you are sincere and unequivocally enthusiastic about your dog’s performance. If you will do that, your dog will respond to your praise, even in the absence of the toy or treat.

A Conditioned Reinforcer (Reward Marker) Must Be Followed by a Toy or Treat

Another form of positive reinforcement is a conditioned reinforcer. Remember Pavlov’s bell? He rang the bell and the dogs drooled. The bell is a “conditioned reinforcer.” Desired behavior is reinforced or strengthened when a conditioned reinforcer is associated with a primary reinforcer (e.g., food).

A conditioned reinforcer is a noise - it can be a clicker or a distinct sound or word used to “mark” instances when your dog makes the correct choice. I use a verbal conditioned reinforcer to “mark” specific behaviors. I chose the word “Yes!” I am distinct and exude an enthusiasm that my dogs recognize when I say “Yes!” More importantly, “if I say it, I pay it!” My dogs know that when I say “Yes!” a treat is on its way -- every time.

In the flow chart, I state that if the dog makes a correct choice, the handler responds with positive reinforcement. Why use a conditioned reinforcer instead of simply handing the dog a treat? Scientific studies show that a distinctive sound (a conditioned reinforcer) that precedes delivery of food (a primary reinforcer) cause dopamine and other chemicals to release in the pleasure and memory centers of the brain. These chemicals cause enjoyment and pleasure.

When a behavior consistently produces these chemicals, the subject starts to enjoy the behavior that leads to the toy or treat.

Read that sentence very carefully. Dogs (and people!) are pleasure seeking. By using a conditioned reinforcer (“Yes!”) paired with a primary reinforcer (e.g., food) you can cause a dog to enjoy the aspects of obedience that are not self-rewarding such as fronts, finishes, and pivots.

Furthermore, a conditioned reinforcer marks and rewards specific behavior. For example, if you teach your dog to run to a bed, and consistently “mark” the exact moment he puts his fourth foot on the bed, he will come to understand that it is the act of getting on the bed that causes the reward to happen. If you simply praise and feed him, he may not understand the behavior that you are rewarding because several things are happening at the same time. You are walking toward him to a deliver the treat with a pleased look on your face and he is turning on the bed, wagging his tail and waiting for you. It’s simply more difficult for a dog to ascertain exactly what behavior caused the reward. For this reason, the chemical release may not occur or is not as intense.

Be aware of some important points when using your conditioned reinforcer. Excited by your dog’s response to the distinctive sound, you may start to randomly use your verbal conditioned reinforcer and not deliver a treat. I watched a trainer heel a dog around the ring chanting “Yes!” as if she were keeping rhythm with the sound of the word. This will cause the sound to become meaningless to the dog. Thus the term, “If you say it, you must pay it!”

Don’t bother using your conditioned reinforcer for activities the dog finds naturally rewarding. If your dog enjoys jumping, let jumping be the reward, you do not need to add anything more to the activity. Instead, use your conditioned reinforcer for the details that are hard to communicate and harder still for the dog to understand, like sitting attentively in heel position, pivoting and then keeping his head up, straight fronts, and holding the dumbbell properly while sitting in front of you.

As dog trainers, we say, and often believe, the dog only does it “for the treat.” However, when you use a conditioned reinforcer properly, you will discover that the sequence of events that lead to the reward becomes enjoyable for your dog. Doing obedience with a dog that enjoys the activity is the most fun of all, for both of you.

Dog Makes an Incorrect Choice

If you believe that dogs are problem solvers, and they learn by trial and error, then sometimes they will make errors. How should you respond to mistakes? Not all errors are the same. Sometimes a dog makes an effort error, and sometimes they make errors due to a lack of effort.

Effort Errors, Characterized by Confusion or Fear

Effort errors are made by dogs that are attentive but appear confused, worried, or fearful. When your dog makes an effort error, he will typically offer one of two responses: (1) he does nothing; or (2) he offers the wrong behavior.

Dog Does Nothing

How should you respond to an inexperienced dog that stares intently at you but does not move when you say “Sit” or the dog that is sitting at go-out but does not move when you say “Jump”?

Dogs do learn when physically moved in the correct direction. This is not true for all species. Cats do not learn by giving them direction nor do chickens or dolphins. Because your dog can learn when physically moved in the correct direction, use it to your advantage!

Be gentle, but firm as you pull up on the dog that fails to sit. When he fails to move in response to your jump command, go get him and physically guide him in the correct direction. He has made an effort error and you are providing him with information about the direction in which he should move.

Dog Offers the Wrong Behavior

Dogs sometimes make effort errors by offering the wrong behavior in an attempt to solve a problem. How should you respond to the dog that heads for glove #2 when sent for glove #3 or the dog that comes straight to you when told to jump over the broad jump?

Dogs have the ability to solve problems. Offering any behavior, even a wrong one, is an attempt to solve a problem. Follow the steps outlined in the article in the next lesson, "A Simple Rule to Train By" by telling your dog he made a mistake, calmly taking him by the collar to guide him back to the position in which he was last right, and starting again by simplifying the task. By following this rule, you are telling your dog that he made a mistake and giving him another opportunity to solve the problem.

Lack of Effort Errors Characterized by Inattentiveness or Disinterest

Not all errors are committed by dogs that are attentive and trying their best. Dogs also make “lack of effort errors” because they are distracted or not interested.

Have you ever called your dog to come, seen him look in your direction, ignore your command and return to sniffing as if to say, “Just a minute, I’m busy.” Have you ever told your excited and/or distracted dog to “Sit,” only to watch him act as if he did not hear you? Have you ever given your dog a command and watched him respond as if he was not even trying to be obedient? These are all examples of “lack of effort errors.”

If you agree that lack of effort errors occur when a dog is not trying, the question becomes how to respond? Dog trainers are quick to use the word “correction.” They answer the question with a simple “I would correct my dog.” What does that mean? The word correction has been used in so many different ways that it has become ambiguous. For example, if you were to tell me that your dog is running around the high jump, and ask me “How would you correct him?” I could not be sure whether you are asking me “how I would fix it” or “what kind of negative response would I use to stop him.”

I use negative reinforcement when a dog is not trying. By definition, reinforcement increases the likelihood that a behavior will occur. Negative reinforcement refers to something the dog wants to stop and wants to prevent!

For example, think about your seatbelt buzzer. That annoying sound increases the likelihood that you will buckle your seatbelt, so, by definition, it is reinforcement. It is negative because you want to make it stop. Thankfully, you know how to do so. When you hear it, buckle up. You can prevent the annoying sound by buckling your seatbelt before you start the car. You are in complete control of the annoying buzz!

How about an underground fence? Smart fence owners teach their dog how to control the sound and electric stimulus the electric fence collar provides. First, they teach their dog where the boundaries of the yard are located. Next, they walk their dog around the boundary, and when the noise occurs, they pull the dog back into the yard (dogs learn by being given direction). When done properly, the dog learns how to stop the sound and electric stimulus (the "aversive") and how to prevent it from occurring again. The dog happily romps around the yard offering the desired behavior (staying inside the delineated boundaries) because he knows how to control the aversive.

A tug on the leash is another example of negative reinforcement. My dogs learn that a tug on the leash can be stopped by looking at me. They also know that they can avoid a tug on the leash by giving me their attention. My dogs know that they are in control of the tug and comfortably give me their full attention.

We have all seen trainers who become frustrated and lose their tempers. We have seen dogs that become nervous and scared when aversive techniques are used. This occurs when the dog does not know how to control the negative events from happening. No one is interested in making their dogs nervous or scared. In fact, we are horrified by the thought of it. That is NOT what I am talking about. I NEVER do anything that my dogs consider offensive until I have, in a calm and systematic way, taught them how to stop it and how to prevent it.

Promise me that you will never do anything to your dog that he finds offensive unless:

- He has made a “Lack of Effort Error”; and

- You have taken the time to teach him how to stop it and how to prevent it.

If you make this promise, your dog will enjoy working with you in the same way the well-trained dog enjoys romping within the confines of a yard with an underground fence.

I have been training dogs for 40 years. I have had 11 Obedience Trial Champions, 5 Field Champions, and earned numerous other titles. I taught obedience classes in Greenville, South Carolina for over 30 years and have helped countless people earn titles on all breeds of dogs. Through it all, I have not grown tired, nor do I take for granted, the skills that dogs allow us to teach them. I have trained dogs to do obedience, fieldwork, service work, therapy work, tracking, and even some detection. No matter what I’m teaching a dog, I follow the principles outlined in this article. By presenting the task as a problem, and helping the dog solve it, I am repeatedly able to teach dogs to become good problem solvers. I am wowed every day by what dogs are able to learn. I hope that you are too!

Read the article "A Simple Rule to Train By"

Did you enjoy the article?

Signup to receive more free training TIPS & TRICKS from Connie.